Ray-Sphere Intersection with Simple Math

Lately I’ve been working on a ray tracer. It’s been going well (or at least as well as I could hope my first renderer could go), but it has been a slow process. I don’t have a formal math background - my day to day work only ever goes as far as enough linear algebra to write shaders, and enough of everything else to implement whatever gameplay I need - and none of this prepared me for the endless pages of ray tracing resources that expected much more math knowledge than I have.

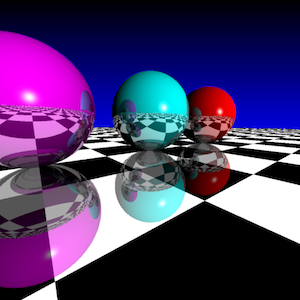

The current output of my ray tracer

So I thought that I’d do my part for the next person who starts writing a ray tracer, and share a bit of what I’ve figured out in as much detail as possible, as clearly as possible.

As the title of this post suggests, the end product of this post will be a function which will take a ray and a sphere, and return both if the they intersect, and if so, the location of the intersection(s).

What you need to know before starting

I’m going to try to keep things as basic as possible. In order to follow this post, you’ll need:

- a basic understanding of trigonometry

- a good handle on vector math (including dot products)

Have you got that? Good! If not, there are a bazillion resources online, go check one of them out before proceeding.

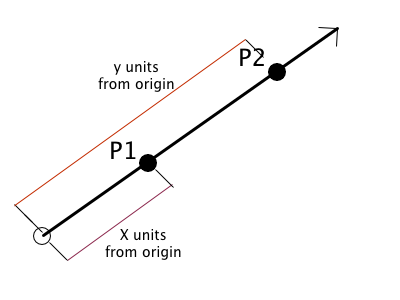

Representing our objects

The first thing we need to get a handle on is how to best represent a ray. If you recall from high school geometry, a ray consists of a single point (the origin), and extends from that origin indefinitely along a direction vector. So for our purposes, a ray is simply a struct which consists of an origin vector and a direction vector.

struct Ray

{

vec3 origin;

vec3 direction;

};

With these 2 vectors, we can represent any point on the ray like this:

Each point will have a specific t value, representing how far along the direction vector the point lies, but the equation remains the same otherwise. This will be important later, so make sure that you try this out on paper and really understand it before proceeding.

Spheres are even simpler. Given that spheres don’t have a direction, all we need is the location of the center point, and the radius of the sphere. This means our sphere object will simply be a struct containing one vector and one float.

struct Sphere

{

vec3 center;

float radius;

};

Turning Vectors into Scalar Values

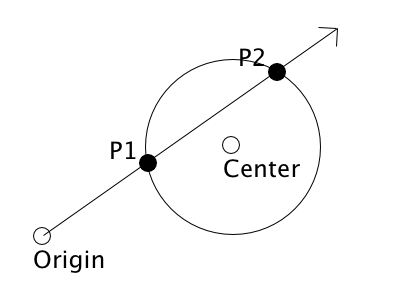

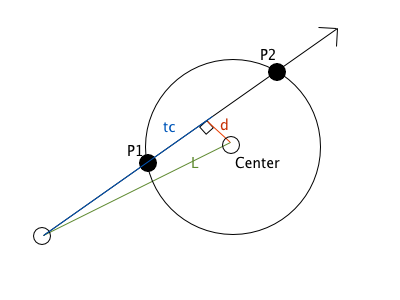

Alright, so the image above shows the general lay of the problem. We have a ray, and a sphere, we know the ray’s origin point, and it’s direction, and we know the location of the sphere’s center point. What we want to do, is determine if the ray will ever intersect the sphere (spoiler: in this tutorial, it will), and if so, where that intersection occurs.

There are 2 points that I haven’t mentioned yet, labelled above as P1 and P2, these are the points that we want to solve for, as both of these represent a point of intersection.

Speaking of those points, remember that we can solve for any point on a ray with the following equation:

So, in order to get the locations of the P0 and P1, all we need to do is find the correct t value for each of them. This is going to make our lives a lot easier, provided you remember a bit of trig (don’t worry, I didn’t either, we’ll go over it as we get to it), since now all we need to do is find 1 number for each point, instead of their exact co-ordinates.

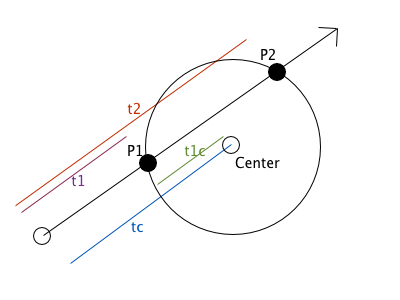

While we’re identifying values to solve for, there are two more t values that are important to us, shown below in blue and green, tc is the distance from the origin to the a point on the ray halfway between the 2 intersection points, and t1c is the distance between t1 and tc. We’ll see why these are important in a minute.

To review these t values have been labelled t1, t2, tc and t1c. t1 and t2 correspond to the points P1 and P2 on our diagram, tc represents the t value to the center and t1c is the distance between P1 and tc.

Finding tc

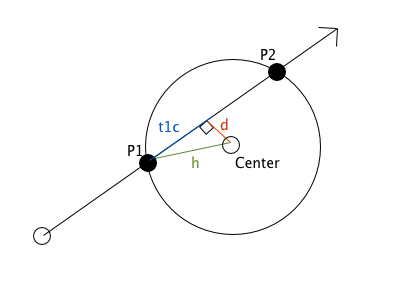

As the headline suggests, the first value we need to solve for is tc. As the diagram below shows, the first step to finding tc is to create a right angle triangle, using tc, the vector from the sphere’s center to the ray’s origin, and a line (d) from the center to the ray.

The first thing we need to find is the length of L. This is simple enough, since we know the positions of both the center and ray origin.

Once we have L, we can use the dot product between L and the ray’s direction in order to get the value for tc. Don’t worry if this seems unintuitive, it had been awhile since I used dot product for projections too. Luckily there are lots of good resources out there that explain this concept (like this one). Moving on though, this means that we have found the value for tc:

This is an important calculation. If the result of this is that tc is less than 0, it means that the ray does not intersect the sphere, and we can bail out of our intersection test early. If it’s not less than 0, we move on.

The last thing we need to do with this triangle is solve for the length of d. This isn’t important for tc, but will be in the next section, so we may as well do it now while we’re still thinking about this triangle.

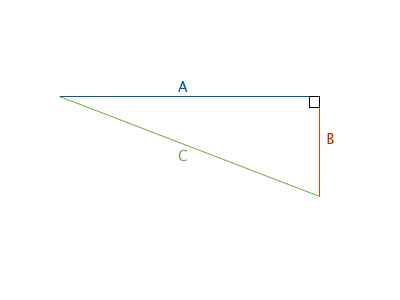

To solve for d, we need to bust out some high school math. If you’re like me, you’ll need a bit of a refresher on this, and I found that it was helpful to rotate our triangle around bit to put it in a more familiar orientation.

Looking familiar yet? If you can remember Pythagoras’ Theorem, you’ll already know where I’m going with this. If not, I’ll help:

We need to find d, which in this case is edge b, so we need to rearrange the equation a bit:

b = √(c² - a²)

Now we just sub in our known values from earlier

Just like tc before it, this is an important calculation. If d is greater than the radius of our sphere, it means that t1c will give us a point outside of the sphere, and our ray doesn’t intersect at all (and we can go home early).

If not, great! Time to move on to the next triangle.

Solving for t1c

Now that we have tc and d, this is actually incredibly easy. Since a² + b² = c², we already know the length of the edge labelled h (it’s the radius of the sphere) and the length of d. Using Pythagoras’ Theorem again gives us:

a = √(c² - b²)

t1c = √(radius² - d²)

Guess that means it’s time to move on to yet another subheading eh?

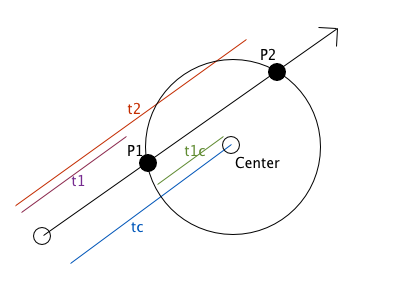

Solving for t1 and t2

Let’s look at our original diagram again:

Notice anything? Now that we have values for t1c and tc, solving for the two variables we actually want is trivial!

t2 = tc + t1c

Which means that all we need to do to get our intersection points is:

P2 = Origin + Direction * t2

An Intersect Function

Congratulations on getting this far! Now that we have all that theory out of the way, it’s time for your prize: a sphere intersection function! Let’s see what that might look like if we simply went step by step using the instructions above:

bool intersec++(Ray* r, Sphere* s)

{

//solve for tc

float L = s->center - r->origin;

float tc = dot(L, r->direction);

if ( tc < 0.0 ) return false;

float d = sqrt((tc*tc) - (L*L));

if ( d > s->radius) return false;

//solve for t1c

float t1c = sqrt( (s->radius * s->radius) - (d*d) );

//solve for intersection points

float t1 = tc - t1c;

float t2 = tc + t1c;

return true;

}For really basic use cases, the above may be sufficient, but there’s an awful lot of wasted effort up there (like calculation t1 and t2 and then not using them). For a ray tracer (the use case that led me to writing this post) it isn’t enough just to know if a ray hits an object, you need to know exactly where the point of contact is.

So let’s rethink the above function (and optimize it in the process):

bool intersect(Ray* r, Sphere* s, float* t1, float *t2)

{

//solve for tc

float L = s->center - r->origin;

float tc = dot(L, r->direction);

if ( tc < 0.0 ) return false;

float d2 = (tc*tc) - (L*L);

float radius2 = s->radius * s->radius;

if ( d2 > radius2) return false;

//solve for t1c

float t1c = sqrt( radius2 - d2 );

//solve for intersection points

*t1 = tc - t1c;

*t2 = tc + t1c;

return true;

}Much better! Not only are we returning getting the solved t values out of the function, but we’ve also managed to get rid of a costly square root operation. This may not seem like a big deal, but when you factor in how many times you will be calling this intersect function, any optimizations you can make pay dividends.

Whew, that was a long post. If anything is unclear, or you spot a mistake (I wrote most of this on a train, it’s very possible something is a bit off) feel free to send me a message on Twitter.

Merry Christmas! :D