X64 Function Hooking by Example

I’ve spent some time recently figuring out how function hooking works. There are tons of great resources available about it, but I’ve noticed that a lot of them are really light on providing example code, and the ones that do provide code tend to link to fully mature hooking frameworks. Usually the linked projects are really impressive, but they aren’t the easiest places to learn the basics from.

Now that I know enough to be dangerous, it seemed like fun to rectify this lack of sample code by building some hooking code from the ground up and walking through how to use that code to hook a running program. My past two blog posts were about making Notepad do weird stuff, so for the sake of variety, this post is going to pick on MSPaint instead.

I’m going to explain how to build 4 example programs. Two of them will show off fundamental hooking concepts by hooking functions in the example code itself. The other two will use those same concepts to hook MSPaint and make it disable the “Edit With Paint3D” button in a running MSPaint instance and force it to always draw with my favourite color (orange).

If you’re only interested in sample code, I’ve published a github repo called Hooking-by-Example which has 14 increasingly complex example programs that demonstrate how function hooking works (or at least, the bits of it that I’ve figured out). Everything that I talk about here (and more) is also demonstrated by the programs in that repo.

WTF is Function Hooking?

Function Hooking is a programming technique that lets you to intercept and redirect function calls in a running application, allowing you to change that program’s runtime behaviour in ways that may not have been intended when the program was initially compiled. It’s a little bit like when a dog gets into a car thinking they’re going to the park and ends up at the vet instead. The dog called goToPark(), but instead unexpectedly ended up inside goToVet() instead. This example isn’t great.

The real fun of function hooking is that you can use it to change the behaviour of programs that you don’t have the source code to, or otherwise can’t recompile. Combined with process injection (which I explained a bit in my last post), you can use function hooks to add entirely new behaviour to any program that you can run on your pc. For example, ReShade uses function hooking to add new postprocessing effects to games, and RenderDoc uses a form of hooking (although not the kind covered here) to allow you to debug graphics code in running applications.

More examples of things you might want to do with function hooking include:

- Logging or replacing function arguments

- Disabling functions

- Measuing the execution time of a function

- Monitoring or replacing data before it gets sent over a network

The only limits are your imagination and ability to read assembly!

How Does It Work?

Let’s say we have a function that adds two Gdiplus::ARGB values together, and we want to use a hook to bypass the addition logic and always return red. The ARGB type is a DWORD that uses a byte for Alpha, Red, Green, and Blue, respectively. Adding two of them together might look like this:

Gdiplus::ARGB AddColors(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right)

{

uint32_t a = min(0xFF000000, (left & 0xFF000000) + (right & 0xFF000000));

uint32_t r = min(0x00FF0000, (left & 0x00FF0000) + (right & 0x00FF0000));

uint32_t g = min(0x0000FF00, (left & 0x0000FF00) + (right & 0x0000FF00));

uint32_t b = min(0x000000FF, (left & 0x000000FF) + (right & 0x000000FF));

return a | r | g | b;

}The function that we want to replace it with (which I’ll call that “payload” function), looks like this:

Gdiplus::ARGB ReturnRed(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right)

{

return 0xffff0000;

}If this was in your own code, you’d add a “return ReturnRed(left, right)” call to the beginning of AddColors(), recompile and call it a day, but what if you couldn’t recompile it? For example, what if it’s part of a closed source third party library, or the program that calls AddColors() is already running?

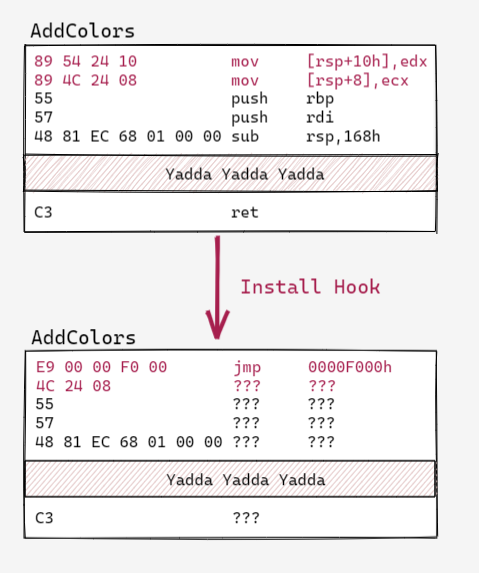

Rather than recompiling, we can use hooking to modify its instruction bytes instead, and replace the first instruction in AddColors() with a jmp to the beginning of the ReturnRed() function. This works even if the function we want to hook comes from a system dll, since DLL code segments are copy-on-write, so there’s no chance of a hook interfering with other processes.

Imagine that the first instruction in ReturnRed() is located 1024 bytes after AddColors() in memory. In assembly, replacing AddColors’ instructions with a jump will look like this:

The jump instruction used here is a relative jump with a 32 bit operand. The opcode is E9, and that’s followed by a 4 byte value that represents how many bytes to jump.

Notice that after the jmp instruction, we’re left with garbage. This is because the process of overwriting the first 5 bytes of AddColors() left a partial instruction in its wake. The first byte of the second instruction was overwritten, but the rest of the bytes are still there, and who knows what instructions those map to. That leaves the rest of the function in an unknown (and likely invalid) state. This doesn’t matter for the example, because the program is going to jump to ReturnRed() before it ever gets to the garbage we just created, but it’s important to keep in mind.

We’ll write some hooks that preserve the hooked function’s original logic later in this post, so don’t worry about that too much right now. For our first example, we’ll build a program that destructively hooks a function, exactly like what’s shown in the diagram above (with some extra sauce to handle 64 bit code).

Example 1: Our First Function Hook

Let’s roll with the example code already provided and write a program that actually redirects program flow from AddColors() to ReturnRed(). The game plan here is to end up with a main() function that looks like this:

//both functions inside the same program as main()

Gdiplus::ARGB AddColors(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right);

Gdiplus::ARGB ReturnRed(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right);

int main()

{

//install a hook in AddColors, going to ReturnRed

InstallHook(AddColors, ReturnRed);

Gdiplus::ARGB col = AddColors(0x00000000, 0x000000FF);

printf("%x\n", col); //will always be 0xFFFF0000

return 0;

}In a 32 bit program, the logic for InstallHook() can be implemented pretty much exactly how the diagram above suggests it would be:

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunction)

{

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(AddColors, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

//32 bit relative jump opcode is E9, takes 1 32 bit operand for jump offset

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

//to fill out the last 4 bytes of jmpInstruction, we need the offset between

//the payload function and the instruction immediately AFTER the jmp instruction

const uint32_t relAddr = (uint32_t)payloadFunction - ((uint32_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

//install the hook

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

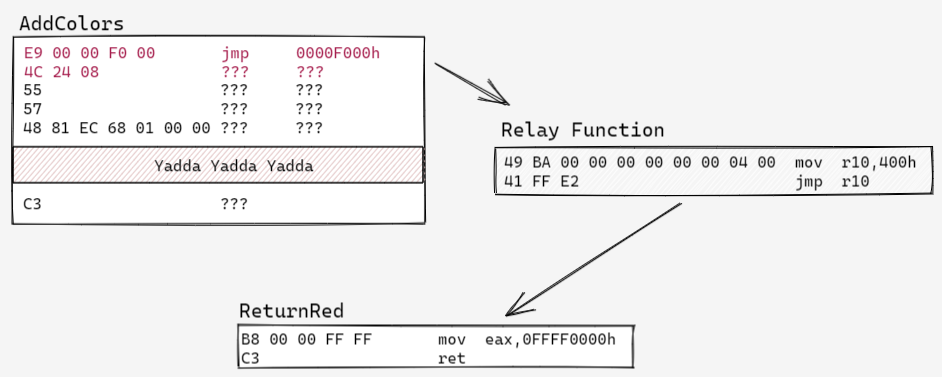

}Things are a bit trickier in 64 bit, because functions can be located so far away from each other in memory that a 32 bit jmp instruction can’t jump that far, meaning that the 5 byte jump written by InstallHook() might be unable to reach the payload function from the hooked function.

There’s no such thing as a 64 bit relative jmp instruction, so the next best option is to jmp to an address stored in a register, like the assembly shown below. Note that this snippet uses the r10 register because it’s one of the few volatile registers that isn’t used for passing function arguments in the Windows x64 calling convention (msdn link)

49 BA 00 00 00 00 00 00 04 00 mov r10,400h

41 FF E2 jmp r10 If we throw this in the beginning of hooked functions instead of the 5 byte jump from before, we’d limit the number of functions that we could hook to those with 13 or more bytes. That’s a singificantly bigger limitation than our 32 bit code, so we’re instead going to write the bytes for this absolute jump somewhere in memory that’s close to the function we’re hooking. Then we’ll have the 5 byte jump we install in that function jump to this absolute jump, instead of straight to the payload function. Minhook refers to this absolute jump as the “relay function,” and I’m going to use that terminology as well.

Writing code to do this little dance is similar to the InstallHook() function shown above, but with a few more steps. The trickiest part of the process is allocating memory for the relay function that’s close enough to the target function to be reachable by a 5 byte jump. I’ve implemented logic for this in a function called AllocatePageNearAddress(). This function is a bit long, so I’ve included it’s implementation in the (expandable) box below, and omitted it from the sample code snippet immediately after that.

AllocPageNearAddress() implementation (click to expand)

void* AllocatePageNearAddress(void* targetAddr)

{

SYSTEM_INFO sysInfo;

GetSystemInfo(&sysInfo);

const uint64_t PAGE_SIZE = sysInfo.dwPageSize;

uint64_t startAddr = (uint64_t(targetAddr) & ~(PAGE_SIZE - 1)); //round down to nearest page boundary

uint64_t minAddr = min(startAddr - 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMinimumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t maxAddr = max(startAddr + 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMaximumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t startPage = (startAddr - (startAddr % PAGE_SIZE));

uint64_t pageOffset = 1;

while (1)

{

uint64_t byteOffset = pageOffset * PAGE_SIZE;

uint64_t highAddr = startPage + byteOffset;

uint64_t lowAddr = (startPage > byteOffset) ? startPage - byteOffset : 0;

bool needsExit = highAddr > maxAddr && lowAddr < minAddr;

if (highAddr < maxAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)highAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr)

return outAddr;

}

if (lowAddr > minAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)lowAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr != nullptr)

return outAddr;

}

pageOffset++;

if (needsExit)

{

break;

}

}

return nullptr;

}void WriteAbsoluteJump64(void* absJumpMemory, void* addrToJumpTo)

{

uint8_t absJumpInstructions[] =

{

0x49, 0xBA, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, //mov r10, addr

0x41, 0xFF, 0xE2 //jmp r10

};

uint64_t addrToJumpTo64 = (uint64_t)addrToJumpTo;

memcpy(&absJumpInstructions[2], &addrToJumpTo64, sizeof(addrToJumpTo64));

memcpy(absJumpMemory, absJumpInstructions, sizeof(absJumpInstructions));

}

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunction)

{

void* relayFuncMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, payloadFunction); //write relay func instructions

//now that the relay function is built, we need to install the E9 jump into the target func,

//this will jump to the relay function

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

//32 bit relative jump opcode is E9, takes 1 32 bit operand for jump offset

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

//to fill out the last 4 bytes of jmpInstruction, we need the offset between

//the relay function and the instruction immediately AFTER the jmp instruction

const uint64_t relAddr = (uint64_t)relayFuncMemory - ((uint64_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

//install the hook

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}With a bit of copy and paste magic, all the code snippets until now can be combined into our first example program. The end result is a small program that ends up calling ReturnRed() whenever we try to call AddColors(). The full code for this example is included in the expandable box below. Note that since this example creates x64 specific instructions for the relay function, it won’t work if it’s built as a 32 bit application. This will be the same for every example we build in this post.

Full Code For Example 1 (click to expand)

#include <Windows.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <memoryapi.h>

#include <gdiplus.h>

#pragma comment (lib, "Gdiplus.lib")

Gdiplus::ARGB AddColors(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right)

{

uint32_t a = min(0xFF000000, (left & 0xFF000000) + (right & 0xFF000000));

uint32_t r = min(0x00FF0000, (left & 0x00FF0000) + (right & 0x00FF0000));

uint32_t g = min(0x0000FF00, (left & 0x0000FF00) + (right & 0x0000FF00));

uint32_t b = min(0x000000FF, (left & 0x000000FF) + (right & 0x000000FF));

return a | r | g | b;

}

Gdiplus::ARGB ReturnRed(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right)

{

return 0xffff0000;

}

void* AllocatePageNearAddress(void* targetAddr)

{

SYSTEM_INFO sysInfo;

GetSystemInfo(&sysInfo);

const uint64_t PAGE_SIZE = sysInfo.dwPageSize;

uint64_t startAddr = (uint64_t(targetAddr) & ~(PAGE_SIZE - 1)); //round down to nearest page boundary

uint64_t minAddr = min(startAddr - 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMinimumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t maxAddr = max(startAddr + 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMaximumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t startPage = (startAddr - (startAddr % PAGE_SIZE));

uint64_t pageOffset = 1;

while (1)

{

uint64_t byteOffset = pageOffset * PAGE_SIZE;

uint64_t highAddr = startPage + byteOffset;

uint64_t lowAddr = (startPage > byteOffset) ? startPage - byteOffset : 0;

bool needsExit = highAddr > maxAddr && lowAddr < minAddr;

if (highAddr < maxAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)highAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr)

return outAddr;

}

if (lowAddr > minAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)lowAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr != nullptr)

return outAddr;

}

pageOffset++;

if (needsExit)

{

break;

}

}

return nullptr;

}

void WriteAbsoluteJump64(void* absJumpMemory, void* addrToJumpTo)

{

uint8_t absJumpInstructions[] =

{

0x49, 0xBA, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, //mov r10, addr

0x41, 0xFF, 0xE2 //jmp r10

};

uint64_t addrToJumpTo64 = (uint64_t)addrToJumpTo;

memcpy(&absJumpInstructions[2], &addrToJumpTo64, sizeof(addrToJumpTo64));

memcpy(absJumpMemory, absJumpInstructions, sizeof(absJumpInstructions));

}

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunction)

{

void* relayFuncMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, payloadFunction); //write relay func instructions

//now that the relay function is built, we need to install the E9 jump into the target func,

//this will jump to the relay function

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

//32 bit relative jump opcode is E9, takes 1 32 bit operand for jump offset

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

//to fill out the last 4 bytes of jmpInstruction, we need the offset between

//the relay function and the instruction immediately AFTER the jmp instruction

const uint64_t relAddr = (uint64_t)relayFuncMemory - ((uint64_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

//install the hook

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}

int main()

{

InstallHook(AddColors, ReturnRed);

Gdiplus::ARGB col = AddColors(0xFF000000, 0x000000FF);

printf("%x\n", col);

return 0;

}This is all we need to know to start installing hooks in programs we have source access to, but there’s an annoying gap between that and being able to hook a running instance of a program. We’ll bridge that gap with the next example.

Example 2: Hooking Functions in a Running Program

The second example program we’re going to build will disable the “Edit With Paint3D” button in a running instance of mspaint.exe.

There are 2 new hurdles we have to overcome in order to install a hook in a running program: getting the target program to execute our hooking logic, and figuring out the address of the function we want to hook. We’ll tackle these in order.

Our mission is to keep the Paint3D button from accomplishing its mission.

Our mission is to keep the Paint3D button from accomplishing its mission.

Getting Code Into a Running Process

The simplest way to get an arbitrary process to execute hooking logic is to build that logic into a DLL and use DLL injection to get that code into the target process’ memory.

The nuts and bolts of how DLL injection work are beyond the scope of this blog post, but if you want to learn more, check out this article. I’ve included the code for a basic DLL injection program in the collapsable box below. This is the code that the example program will use to inject its dll into mspaint.exe.

Full DLL Injection Code (click to expand)

//Injector_LoadLibrary is a dll injector that uses LoadLibraryA to inject a dll into a running process

// usage: Injector_LoadLibrary <process name> <path to dll>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <Windows.h>

#include <TlHelp32.h> //for PROCESSENTRY32, needs to be included after windows.h

void printHelp()

{

printf("Injector_LoadLibrary\nUsage: Injector_LoadLibrary <process name> <path to dll>\n");

}

void createRemoteThread(DWORD processID, const char* dllPath)

{

HANDLE handle = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION | //Needed to get a process' token

PROCESS_CREATE_THREAD | //for obvious reasons

PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | //required to perform operations on address space of process (like WriteProcessMemory)

PROCESS_VM_WRITE, //required for WriteProcessMemory

FALSE, //don't inherit handle

processID);

if (handle == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not open process with pid: %lu\n", processID);

return;

}

//once the process is open, we need to write the name of our dll to that process' memory

size_t dllPathLen = strlen(dllPath);

void* dllPathRemote = VirtualAllocEx(

handle,

NULL, //let the system decide where to allocate the memory

dllPathLen,

MEM_COMMIT, //actually commit the virtual memory

PAGE_READWRITE); //mem access for committed page

if (!dllPathRemote)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not allocate %zd bytes in process with pid: %lu\n", dllPathLen, processID);

return;

}

BOOL writeSucceeded = WriteProcessMemory(

handle,

dllPathRemote,

dllPath,

dllPathLen,

NULL);

if (!writeSucceeded)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not write %zd bytes to process with pid %lu\n", dllPathLen, processID);

return;

}

//now get address of LoadLibraryW function inside Kernel32.dll

//TEXT macro "Identifies a string as Unicode when UNICODE is defined by a preprocessor directive during compilation. Otherwise, ANSI string"

PTHREAD_START_ROUTINE loadLibraryFunc = (PTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(TEXT("Kernel32.dll")), "LoadLibraryA");

if (loadLibraryFunc == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not find LoadLibraryA function inside kernel32.dll\n");

return;

}

//now create a thread in remote process that loads our target dll using LoadLibraryA

HANDLE remoteThread = CreateRemoteThread(

handle,

NULL, //default thread security

0, //stack size for thread

loadLibraryFunc, //pointer to start of thread function (for us, LoadLibraryA)

dllPathRemote, //pointer to variable being passed to thread function

0, //0 means the thread runs immediately after creation

NULL); //we don't care about getting back the thread identifier

if (remoteThread == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not create remote thread.\n");

return;

}

else

{

fprintf(stdout, "Success! remote thread started in process %d\n", processID);

}

// Wait for the remote thread to terminate

WaitForSingleObject(remoteThread, INFINITE);

//once we're done, free the memory we allocated in the remote process for the dllPathname, and shut down

VirtualFreeEx(handle, dllPathRemote, 0, MEM_RELEASE);

CloseHandle(remoteThread);

CloseHandle(handle);

}

DWORD findPidByName(const char* name)

{

HANDLE h;

PROCESSENTRY32 singleProcess;

h = CreateToolhelp32Snapshot( //takes a snapshot of specified processes

TH32CS_SNAPPROCESS, //get all processes

0); //ignored for SNAPPROCESS

singleProcess.dwSize = sizeof(PROCESSENTRY32);

do {

if (strcmp(singleProcess.szExeFile, name) == 0)

{

DWORD pid = singleProcess.th32ProcessID;

printf("PID Found: %lu\n", pid);

CloseHandle(h);

return pid;

}

} while (Process32Next(h, &singleProcess));

CloseHandle(h);

return 0;

}

int main(int argc, const char** argv)

{

if (argc != 3)

{

printHelp();

}

createRemoteThread(findPidByName(argv[1]), argv[2]);

return 0;

}The code for the dll we’re going to inject is basically identical to the last example except that main() will be replaced by DllMain(), and we need to do some extra work to get a pointer to the function we want to hook. With those concerns in mind, the skeleton of Example 2’s dll looks like this:

//source for a hooking dll that will be injected into mspaint.exe

#include <Windows.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <Psapi.h>

void* AllocatePageNearAddress(void* targetAddr)

{

//same as before

}

void WriteAbsoluteJump64(void* absJumpMemory, void* addrToJumpTo)

{

//same as before

}

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunction)

{

//same as before

}

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

if (ul_reason_for_call == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

InstallHook(0x0, 0x0); //we'll fill this in later

}

return true;

}What Function Do We Need to Hook?

Since our goal is to disable the “Edit With Paint3D” button, we need to find the mspaint.exe function that handles that button press. We know that the “Edit With Paint3D” button eventually launches a Paint3D process, so we can be reasonably sure that a function like CreateProcessA() or OpenProcess() gets called at some point during the button handling function. Blindly hooking either of these functions and redirecting them to an empty function doesn’t work (I tried), but throwing some breakpoints on them is as good a place to start as any.

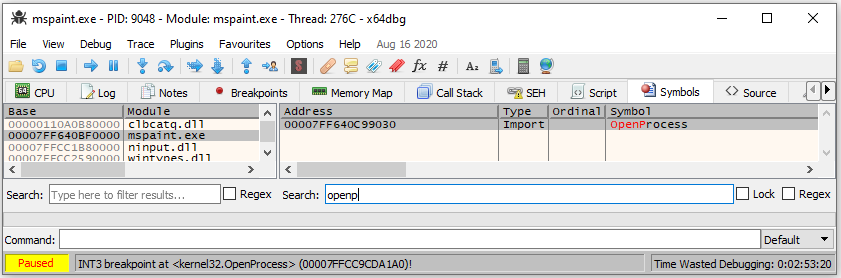

If we look at the functions imported by mspaint in a debugger (like x64dbg), we can see that it is in fact importing OpenProcess(), so our first step is to throw a breakpoint there and then see what happens when we press the paint3d button.

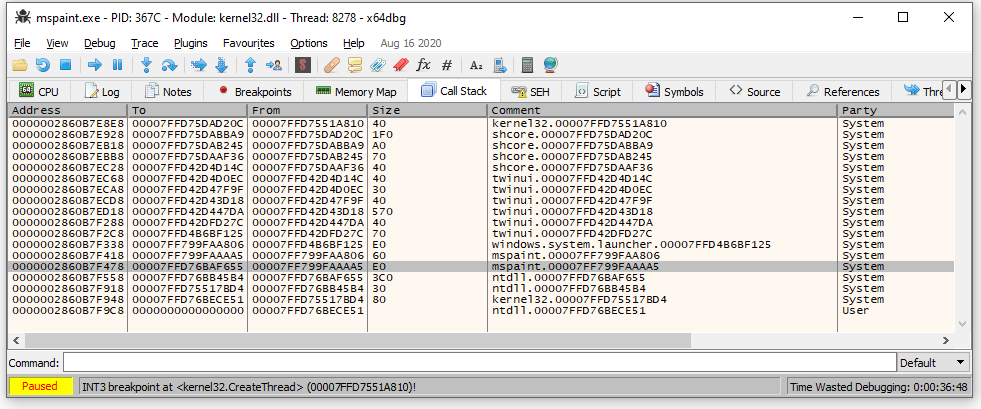

It turns out that our breakpoint does get hit in response to the button click, which is fantastic. If we switch over to the callstack view while we’re stopped at the breakpoint, we can see a couple of mspaint.exe functions much higher up in the stack. It’s possible that the one of these that’s highest in the callstack is the button handler function we’re after.

Going to the address shown for that function brings us into middle of a function body. What we’re after is the relative virtual address (RVA) of the beginning of this function. x64dbg makes this really easy. All we need to do is scroll up until we find the first instruction for the function, then right click on the address of that instruction and select “Copy->RVA.” In my version of mspaint.exe, the RVA of this function is 0x4AA40.

I’m going to save us some trial and error here and reveal that 0x4AA40 ends up not being the address we need. The real button handler runs on a different thread. Hooking 0x4AA40 and redirecting it to an empty function disables the Paint3D button, but only if the current document is empty.

I wish I had a better procedure to share, but my next step after realizing the above was to retry the same procedure except draw something in paint before I clicked the Paint3D button. The callstack I got then had a number of calls inside uiribbon.dll, and the highest mspaint.exe function in that stack ended up being the button handler. Its RVA was 0x6C6F0.

Turning an RVA Into a Runtime Memory Address

RVAs are addresses which are relative to the base address of the module they’re located in. Since programs (and individual modules, thanks to ASLR) can be loaded into memory at different locations across multiple runs of the same program, having the RVA of a function means that we can reliably get that function’s address, no matter where the process is loaded in memory.

In this case, our target function is implemented inside the base module of the process (since it isn’t imported from a dll), so we need to find the base address of the mspaint.exe module. We can do this with the function below.

uint64_t GetBaseModuleForProcess()

{

HANDLE process = GetCurrentProcess();

HMODULE processModules[1024];

DWORD numBytesWrittenInModuleArray = 0;

EnumProcessModules(process, processModules, sizeof(HMODULE) * 1024, &numBytesWrittenInModuleArray);

DWORD numRemoteModules = numBytesWrittenInModuleArray / sizeof(HMODULE);

CHAR processName[256];

GetModuleFileNameEx(process, NULL, processName, 256); //a null module handle gets the process name

_strlwr_s(processName, 256);

HMODULE module = 0; //An HMODULE is the DLL's base address

for (DWORD i = 0; i < numRemoteModules; ++i)

{

CHAR moduleName[256];

CHAR absoluteModuleName[256];

GetModuleFileNameEx(process, processModules[i], moduleName, 256);

_fullpath(absoluteModuleName, moduleName, 256);

_strlwr_s(absoluteModuleName, 256);

if (strcmp(processName, absoluteModuleName) == 0)

{

module = processModules[i];

break;

}

}

return (uint64_t)module;

}HMODULES are actually pointers to the location of a module in memory, so the cast to a uint64_t in the above example is mostly for convenience. In order to get the address of our target function, we’ll need to add the function’s RVA to this base module address.

void* GetFunc2HookAddr()

{

uint64_t functionRVA = 0x6C6F0;

uint64_t func2HookAddr = GetBaseModuleForProcess() + functionRVA;

return (void*)func2HookAddr;

}If we were hooking a function that was imported from a dll, we’d need to modify the GetBaseMdouleForProcess() function to let us specify the name of the module that we were after, rather than being hardcoded to find the base. We’ll do this in the fourth example in this post, but you can also see an example of this in the code for my hooking-by-example repo here.

Putting It All Together

Now that we have a function to hook, we need to do is to redirect it to an empty payload function to disable it. This is straightforward as it sounds:

int NullPaint3DButtonHandler()

{

return 0;

}

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

if (ul_reason_for_call == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

InstallHook(GetFunc2HookAddr(), NullPaint3DButtonHandler);

}

return true;

}We got a bit lucky here because the button handling function doesn’t have a significant return value (or at least, returning 0 from it is valid). The smart way to approach this would probably be to spend some time in the debugger really understanding what this button handling function does, so that we could write a payload that we knew wasn’t going to break anything, but sometimes it’s better to be lucky than smart.

All we need to do to finish things off is add the implementation for GetFunc2HookAddr() and the payload function into our example dll. The end result is a dll that disables the “Edit with Paint3D” button when injected into mspaint, exactly as we planned. The full source for this example is in the collapsable bow below.

Full Code for Example 2 (click to expand)

#include <Windows.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <Psapi.h>

void* AllocatePageNearAddress(void* targetAddr)

{

SYSTEM_INFO sysInfo;

GetSystemInfo(&sysInfo);

const uint64_t PAGE_SIZE = sysInfo.dwPageSize;

uint64_t startAddr = (uint64_t(targetAddr) & ~(PAGE_SIZE - 1)); //round down to nearest page boundary

uint64_t minAddr = min(startAddr - 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMinimumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t maxAddr = max(startAddr + 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMaximumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t startPage = (startAddr - (startAddr % PAGE_SIZE));

uint64_t pageOffset = 1;

while (1)

{

uint64_t byteOffset = pageOffset * PAGE_SIZE;

uint64_t highAddr = startPage + byteOffset;

uint64_t lowAddr = (startPage > byteOffset) ? startPage - byteOffset : 0;

bool needsExit = highAddr > maxAddr && lowAddr < minAddr;

if (highAddr < maxAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)highAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr)

return outAddr;

}

if (lowAddr > minAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)lowAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr != nullptr)

return outAddr;

}

pageOffset++;

if (needsExit)

{

break;

}

}

return nullptr;

}

uint64_t GetBaseModuleForProcess()

{

HANDLE process = GetCurrentProcess();

HMODULE processModules[1024];

DWORD numBytesWrittenInModuleArray = 0;

EnumProcessModules(process, processModules, sizeof(HMODULE) * 1024, &numBytesWrittenInModuleArray);

DWORD numRemoteModules = numBytesWrittenInModuleArray / sizeof(HMODULE);

CHAR processName[256];

GetModuleFileNameEx(process, NULL, processName, 256); //a null module handle gets the process name

_strlwr_s(processName, 256);

HMODULE module = 0; //An HMODULE is the DLL's base address

for (DWORD i = 0; i < numRemoteModules; ++i)

{

CHAR moduleName[256];

CHAR absoluteModuleName[256];

GetModuleFileNameEx(process, processModules[i], moduleName, 256);

_fullpath(absoluteModuleName, moduleName, 256);

_strlwr_s(absoluteModuleName, 256);

if (strcmp(processName, absoluteModuleName) == 0)

{

module = processModules[i];

break;

}

}

return (uint64_t)module;

}

void WriteAbsoluteJump64(void* absJumpMemory, void* addrToJumpTo)

{

uint8_t absJumpInstructions[] = { 0x49, 0xBA, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x41, 0xFF, 0xE2 };

uint64_t addrToJumpTo64 = (uint64_t)addrToJumpTo;

memcpy(&absJumpInstructions[2], &addrToJumpTo64, sizeof(addrToJumpTo64));

memcpy(absJumpMemory, absJumpInstructions, sizeof(absJumpInstructions));

}

void InstallHook(void* targetFunction, void* payloadFunction)

{

uint64_t functionRVA = 0x6C6F0;

uint64_t func2HookAddr = GetBaseModuleForProcess() + functionRVA;

void* func2hook = (void*)func2HookAddr;

void* relayFuncMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, NullPaint3DButtonHandler); //write relay func instructions

//now that the relay function is built, we need to install the E9 jump into the target func,

//this will jump to the relay function

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

const uint64_t relAddr = (uint64_t)relayFuncMemory - ((uint64_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

//install the hook

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}

void* GetFunc2HookAddr()

{

uint64_t functionRVA = 0x6C6F0;

uint64_t func2HookAddr = GetBaseModuleForProcess() + functionRVA;

return (void*)func2HookAddr;

}

int NullPaint3DButtonHandler()

{

return 0;

}

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

if (ul_reason_for_call == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

InstallHook(GetFunc2HookAddr(), NullPaint3DButtonHandler);

}

return true;

}Function Hooking for Big Kids

The previous examples technically hooked a couple functions, but did so at the cost of destroying their original functionality. This meant that we couldn’t do things like modify function arguments being passed to the original functions, or add logging while preserving the original logic of the hooked programs. Real function hooking doesn’t have to make this trade, and our next two examples won’t either.

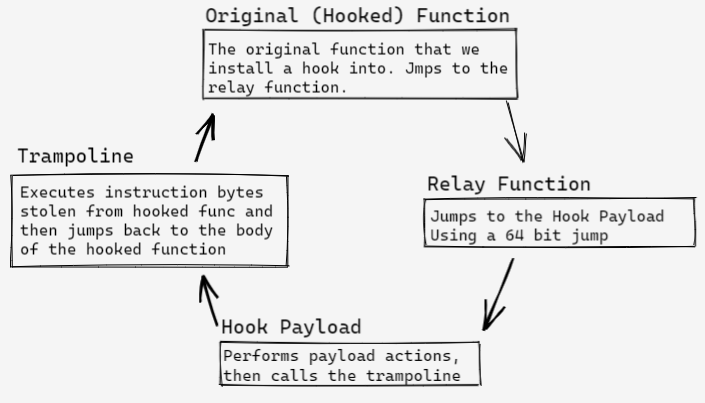

So far, the hooks we’ve created have had 3 parts: the hooked function, the relay function, and the hook payload. Now we need to add another step in this process, called a trampoline. With this new step, our hook process looks like this:

Rather than simply replace the initial instructions in the hooked function, we’re going to use those instructions to build a trampoline that we can call from a payload function when we want to execute the original version of the hooked function. A hook payload that uses a trampoline might look like this:

Gdiplus::ARGB(*AddColorsTrampoline)(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right);

Gdiplus::ARGB AddColorHookPayload(Gdiplus::ARGB left, Gdiplus::ARGB right)

{

//perform some new action

printf("Hook executed\n");

//replace one of the arguments being used to call

//the hooked function

return AddColorsTrampoline(0xFFFF0000, right);

}At a super high level, trampolines need to do two things:

- Execute the instructions that were overwritten when the hook jmp was installed in the hooked function.

- Jump back to the body of the hooked function AFTER the installed jump instruction, so that the rest of the function can continue like normal.

The first item on this list is really easy to get working for contrived cases, but really difficult to get right for real world use. Consider the following assembly (shown with the addresses of the instructions on the left):

EasyCase:

00007FF7F2691FF0 48 89 4C 24 08 mov qword ptr [rsp+8],rcx

00007FF7F2691FF5 55 push rbp

00007FF7F2691FF6 57 push rdi

00007FF7F2691FF7 48 81 EC 08 01 00 00 sub rsp,108h

00007FF7F2691FFE 48 8D 6C 24 20 lea rbp,[rsp+20h]

[Rest of function omitted]This is an example of the “easy” case for creating a trampoline. The first 5 bytes of the function belong to one instruction, and that instruction doesn’t rely on any rip-relative addressing. All we need to do to make a trampoline for this function is copy the first 5 bytes to a buffer before we overwrite them with our hook, and then add a jump to 00007FF6E3521FF5 immediately after it. In assembly, this might look like this:

Trampoline:

48 89 4C 24 08 mov qword ptr [rsp+8],rcx

49 BA F5 1F 69 F2 F7 7F 00 00 mov r10,7FF7F2691FF5h

41 FF E2 jmp r10 Functions that are harder to hook with a trampoline might have multiple instructions contained in their first 5 bytes, or use instructions with relative operands, like jumps or rip-relative addresses. The snippet below shows an example of a function that has some of these issues.

HardCase:

00007FF72B1F1390 85 C9 test ecx,ecx

00007FF72B1F1392 74 26 je TargetFunc+2Ah (07FF72B1F13BAh)

00007FF72B1F1394 83 F9 01 cmp ecx,1

00007FF72B1F1397 74 0C je TargetFunc+15h (07FF72B1F13A5h)

[Rest of function omitted]In order to build a trampoline for this function, we’re going to have to get our hands dirty. First of all, we’re going to need to steal the first 7 bytes of this function instead of the first 5, so that we can execute whole instructions in our trampoline. Second, we’re going to need to do something about the je at 00007FF72B1F1392h, since it won’t make sense to do a relative jump once we relocate the instruction.

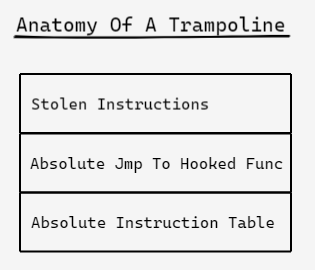

The next section of this post is going to walk through how to write code that deals with these “hard” issues, but as a bit of a teaser, here’s what the trampoline for this will look like:

HardCase_Trampoline:

85 C9 test ecx,ecx

74 10 je 000001FA4B770021 ; rewritten jump

83 F9 01 cmp ecx,1

49 BA 97 13 09 C0 F6 7F 00 00 mov r10, 7FF6C0091397h ; Jump to hooked function body

41 FF E2 jmp r10

49 BA BA 13 09 C0 F6 7F 00 00 mov r10, 7FF6C00913BAh ; Absolute Instruction Table Starts Here

41 FF E2 jmp r10 This trampoline can be thought of as being made up of three sections (like a “jump sandwich”, which I thought was very funny when I wrote this at 5 am). It starts with the stolen bytes from the hooked instruction, with the relative instructions rewritten to jump to a later part of the trampoline. The meat of the sandwich is an absolute jump that goes back to the body of the hooked function (to an address after the jmp we installed for the hook). Finally, the bottom of the trampoline are absolute jumps (or calls, if we had any) that go to the addresses that the relative jumps/calls in the stolen bytes actually want to go.

Other sources refer to the absolute instruction table as a jump table, but I’m giving it a fancy name because it’s not going to contain jump instructions exclusively.

Example 3: Building a Trampoline For Code We Can Recompile

We just saw the rough skeleton of the trampoline we’re going to build, now it’s time to write the code to build it. Roughly speaking, our plan of attack looks like this:

- “Steal” the first 5+ bytes (rounded up to the nearest whole instruction) of the function we want to hook.

- Fixup any rip-relative addressing (like lea rcx,[rip+0xbeef])

- For each relative jump or call instruction, calculate the address that it originally intended to reference, and add an absolute jmp/call to that address in the Absolute Instruction Table.

- Rewrite the relative instructions in the stolen bytes to jump to their corresponding entry in the Absolute Instruction Table.

- Write a jump back to the 6th byte of the hooked function immediately after the stolen instruction bytes, to continue executing the hooked function once the trampoline ends.

These steps won’t be completed sequentially in our final program, but I’ve split them out into discrete steps to make explaining things easier.

For a bit of context, here’s what our final InstallHook() function is going to look like when we’re done. We’re going to be constructing a BuildTrampoline() function which will be given a pointer to some memory to write a trampoline into, and not much else. BuildTrampoline() is going to be called from a modified version of the InstallHook() function we had in our earlier example. Notice that BuildTrampoline() will also return the size, in bytes, of the trampoline that it creates.

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunc, void** trampolinePtr)

{

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

void* hookMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

uint32_t trampolineSize = BuildTrampoline(func2hook, hookMemory);

*trampolinePtr = hookMemory;

//create the relay function

void* relayFuncMemory = (char*)hookMemory + trampolineSize;

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, payloadFunc); //write relay func instructions

//install the hook

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

const int32_t relAddr = (int32_t)relayFuncMemory - ((int32_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}The intended use case for the trampoline pointer is to allow payload functions to call trampolines like regular functions, as shown in the snippet below.

void(*TargetFuncTrampoline)(int, float) = nullptr;

void HookPayload(int x, float y)

{

printf("Hook executed\n");

TargetFuncTrampoline(x+1, y);

}Notice that we’re going to build the trampoline in the same “near” memory that the relay function is currently being constructed in. That’s going to make dealing with the rip-relative addressing a lot easier when we get it to it.

Step 1: Stealing Instruction Bytes

In order for our trampoline to work at all, it needs to execute the instructions that are overwritten when we install our hook. To do this, we need to “steal” these instruction bytes from our target function before overwriting them. The verb “steal” is important here - we’re not only going to copy these instruction bytes, we’re also going to replace them with 1 byte NOPs in the target function. That way won’t wind up with any partial instructions when we install the hook jump.

To make sure we steal whole instructions, we need to use a disassembly library. The rest of this article is going to use the Capstone library for all disassembly tasks. Any disassembler will do, but Capstone has some features that are going to make our life easier later on.

This snippet shos how to steal the instructions contained within the first 5 bytes of a target function using Capstone. The StealBytes() function returns a struct with some additional data about the stolen instructions which we’ll use later.

struct X64Instructions

{

cs_insn* instructions;

uint32_t numInstructions;

uint32_t numBytes;

};

X64Instructions StealBytes(void* function)

{

// Disassemble stolen bytes

csh handle;

cs_open(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64, &handle);

cs_option(handle, CS_OPT_DETAIL, CS_OPT_ON); // we need details enabled for relocating RIP relative instrs

size_t count;

cs_insn* disassembledInstructions; //allocated by cs_disasm, needs to be manually freed later

count = cs_disasm(handle, (uint8_t*)function, 20, (uint64_t)function, 20, &disassembledInstructions);

//get the instructions covered by the first 5 bytes of the original function

uint32_t byteCount = 0;

uint32_t stolenInstrCount = 0;

for (int32_t i = 0; i < count; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = disassembledInstructions[i];

byteCount += inst.size;

stolenInstrCount++;

if (byteCount >= 5) break;

}

//replace instructions in target func wtih NOPs

memset(function, 0x90, byteCount);

cs_close(&handle);

return { disassembledInstructions, stolenInstrCount, byteCount };

}We’ll call this function right at the start of BuildTrampoline(), so it’s about time we started writing that function too. I’ve found the most intuitive way to structure BuildTrampoline() is to create 3 pointers at the start, each pointing to the next available location in each of the three sections of our trampoline memory. Whenever we write to a location pointed to by one of these pointers, we’ll then increment the pointer by that many bytes, so each of them is always pointing to an available memory address.

uint32_t BuildTrampoline(void* func2hook, void* dstMemForTrampoline)

{

X64Instructions stolenInstrs = StealBytes(func2hook);

uint8_t* stolenByteMem = (uint8_t*)dstMemForTrampoline;

uint8_t* jumpBackMem = stolenByteMem + stolenInstrs.numBytes;

uint8_t* absTableMem = jumpBackMem + 13; //13 is the size of the 64 bit mov/jmp instruction pair at jumpBackMem

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

//perform any fixup logic to the stolen instructions here

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}

//write jump back to hooked func

free(stolenInstrs.instructions);

return uint32_t( (uint8_t*)absTableMem - dstMemForTrampoline);

}If we only ever needed to hook “easy” functions (as defined earlier), we could skip down to the last step in our trampoline creation procedure now. There’s a lot more legroom required to support less-than-easy functions though.

Step 2: Fixing up RIP-Relative Addressing

One case where our naiive trampoline building function will fail is if any of the stolen instructions contain rip-relative addressing. In x64, there are a lot of instructions that do this, but the easiest example is a function that calls printf.

void PrintHaha()

{

printf("Haha\n");

}On my machine, the generated assembly uses an lea instruction to load the string location before the call to printf. The assembly string generated by visual studio makes it look like the lea call is grabbing an absolute address, but the instruction bytes reveal that we’re actually computing the address of the “Haha\n” string by adding an offset to the current value of the instruction pointer.

PrintHaha:

00007FFCB54211E0 48 8D 0D F9 1F 00 00 lea rcx,[string "Haha\n" (07FFCB54231E0h)]

00007FFCB54211E7 E9 24 FE FF FF jmp printf (07FFCB5421010h) If we steal the lea instruction verbatim, we’ll get garbage data when we executed the stolen instruction because our instruction pointer will be at a different address. In order to actually use instructions that have rip-relative addressing in our trampoline, we need to fix up the offsets they use to be relative to our trampoline memory.

The first step of this is to detect when an instruction contains a rip-relative operand. Capstone makes this easy.

bool IsRIPRelativeInstr(cs_insn& inst)

{

cs_x86* x86 = &(inst.detail->x86);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < inst.detail->x86.op_count; i++)

{

cs_x86_op* op = &(x86->operands[i]);

//mem type is rip relative, like lea rcx,[rip+0xbeef]

if (op->type == X86_OP_MEM)

{

//if we're relative to rip

return op->mem.base == X86_REG_RIP;

}

}

return false;

}Relocating an instruction that’s been identified as having a rip-relative operand is a bit more of a bear. Remember how I mentioned that we’re going to put our trampoline in memory that’s within a 32 bit jump of our target function? That’s to try to avoid cases where the new offset we compute is too large to be stored in the existing instruction’s operand.

template<class T>

T GetDisplacement(cs_insn* inst, uint8_t offset)

{

T disp;

memcpy(&disp, &inst->bytes[offset], sizeof(T));

return disp;

}

//rewrite instruction bytes so that any RIP-relative displacement operands

//make sense with wherever we're relocating to

void RelocateInstruction(cs_insn* inst, void* dstLocation)

{

cs_x86* x86 = &(inst->detail->x86);

uint8_t offset = x86->encoding.disp_offset;

uint64_t displacement = inst->bytes[x86->encoding.disp_offset];

switch (x86->encoding.disp_size)

{

case 1:

{

int8_t disp = GetDisplacement<uint8_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address;

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 1);

}break;

case 2:

{

int16_t disp = GetDisplacement<uint16_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address;

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 2);

}break;

case 4:

{

int32_t disp = GetDisplacement<int32_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address;

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 4);

}break;

}

}Shout out to the polyhook source that I stole this logic from.

Plugging these functions into the BuildTrampoline() logic requires adding a check and a function call to the for loop that processes our stolen instructions.

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

//perform any fixup logic to the stolen instructions here

if (IsRIPRelativeInstr(inst))

{

RelocateInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem);

}

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}Now we can hook our little printf function with wild abandon!

Step 3: Building the Absolute Instruction Table

Next we need to deal with any relative jump or call instructions in our stolen bytes. After all “jump 10 bytes from here” doesn’t mean very much when the instruction has been moved to a new “here.” I have no idea how to handle loop instructions, so the example code will only deal with jmp and call instructions.

Like with the rip-relative operands, the first thing we need to do is identify whether an instruction is one of the flavors of jmp or call that we care about. Identifying relative calls is pretty easy, because there aren’t that many varieties of call instructions, and all the relative versions have opcodes that start with 0xE8.

bool IsRelativeCall(cs_insn& inst)

{

bool isCall = inst.id == X86_INS_CALL;

bool startsWithE8 = inst.bytes[0] == 0xE8;

return isCall && startsWithE8;

}Identifying jmps is a little harder because there are lots of different types of jmp instructions. Since conditional jumps only come in relative versions, if an instruction’s id says it’s a conditional jump, we know it uses relative addressing. The unconditional “jmp” instruction can use relative addressing, but it can also do things like jump to an address in a register. Thankfully, the behaviour of a jmp is dictated by it’s opcode bytes. Relative jmps start with 0xEB and 0xE9.

bool IsRelativeJump(cs_insn& inst)

{

bool isAnyJumpInstruction = inst.id >= X86_INS_JAE && inst.id <= X86_INS_JS;

bool isJmp = inst.id == X86_INS_JMP;

bool startsWithEBorE9 = inst.bytes[0] == 0xEB || inst.bytes[0] == 0xE9;

return isJmp ? startsWithEBorE9 : isAnyJumpInstruction;

}We can use these two functions to quickly identify any stolen instructions that are going to require extra attention:

for (int i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

if (inst.id >= X86_INS_LOOP && inst.id <= X86_INS_LOOPNE)

{

return 0; //bail out on loop instructions, I don't have a good way of handling them

}

if (IsRIPRelativeInstr(inst))

{

RelocateInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem);

}

else if (IsRelativeJump(inst))

{

}

else if (IsRelativeCall(inst))

{

}

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}

Next We need to figure out the address that the original instruction wanted to go to, and add an absolute jump (or call) to that address to our Absolute Instruction Table. The Capstone library handles calculating the target address of relative instructions for us automatically, which is handy.

Jumps are easier to handle than calls, so we’ll start there. We’ll reuse the WriteAbsoluteJump64 function from earlier in this post to make the code a bit more concise.

uint32_t AddJmpToAbsTable(cs_insn& jmp, uint8_t* absTableMem)

{

char* targetAddrStr = jmp.op_str; //where the instruction intended to go

uint64_t targetAddr = _strtoui64(targetAddrStr, NULL, 0);

WriteAbsoluteJump64(absTableMem, (void*)targetAddr);

return 13; //size of mov/jmp instrs for absolute jump

}Note that this function doesn’t rewrite the existing jump instruction, it only adds an absolute version of it to the absolute instruction table (AIT). We’ll handle pointing the original jump to this AIT entry later in this post.

Dealing with calls is a bit different. If we just add an absolute call instruction to our AIT, when that call returns, we’ll wind up at the next jump in the table. That would be bad, so instead we also need to add a jump instruction after our absolute calls to redirect program flow to somewhere more helpful. In this case, we’ll jump to the middle of our trampoline, which is the jump back to the hooked function’s body.

uint32_t AddCallToAbsTable(cs_insn& call, uint8_t* absTableMem, uint8_t* jumpBackToHookedFunc)

{

char* targetAddrStr = call.op_str; //where the instruction intended to go

uint64_t targetAddr = _strtoui64(targetAddrStr, NULL, 0);

uint8_t* dstMem = absTableMem;

uint8_t callAsmBytes[] =

{

0x49, 0xBA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, //movabs 64 bit value into r10

0x41, 0xFF, 0xD2, //call r10

};

memcpy(&callAsmBytes[2], &targetAddr, sizeof(void*));

memcpy(dstMem, &callAsmBytes, sizeof(callAsmBytes));

dstMem += sizeof(callAsmBytes);

//after the call, we need to add a second 2 byte jump, which will jump back to the

//final jump of the stolen bytes

uint8_t jmpBytes[2] = { 0xEB, jumpBackToHookedFunc - (absTableMem + sizeof(jmpBytes)) };

memcpy(dstMem, jmpBytes, sizeof(jmpBytes));

return sizeof(callAsmBytes) + sizeof(jmpBytes); //15

}You’ve probably noticed that both of these functions return the number of bytes that they wrote to the AIT. This is so we can increment the absTableMem pointer in BuildTrampoline(). These calls should be added inside the IsRelativeJump()/IsRelativeCall() conditionals in the BuildTrampoline() function.

for (int i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

if (inst.id >= X86_INS_LOOP && inst.id <= X86_INS_LOOPNE)

{

return 0; //bail out on loop instructions, I don't have a good way of handling them

}

if (IsRIPRelativeInstr(inst))

{

RelocateInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem);

}

else if (IsRelativeJump(inst))

{

uint32_t aitSize = AddJmpToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem);

//rewrite inst here

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

else if (IsRelativeCall(inst))

{

uint32_t aitSize = AddCallToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem, jumpBackMem);

//rewrite inst here

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}

Step 4: Rewriting Jumps/Calls to Use the AIT.

Adding instructions to the Absolute Instruction Table is great and all, but in order for any of that work to matter, we also need to rewrite our stolen relative instructions to actually go to the AIT. Similar to the last step, this needs to be handled differently for jumps vs calls.

Calls are the easier of the two to rewrite, so we’ll start with them. Since all call instructions are unconditional, we can replace any relative calls with jumps to the appropriate address inside the AIT. We know that our trampoline won’t be larger than 255 bytes, so we can use a 2 byte jmp instruction for this. We don’t want to change the size of the call instruction we’re rewriting, so we’ll first replace all the bytes for that instruction with NOPs. That way, if we rewrite a 4 byte call with a 2 byte jmp, we haven’t added garbage instructions to the trampoline.

void RewriteCallInstruction(cs_insn* instr, uint8_t* instrPtr, uint8_t* absTableEntry)

{

uint8_t distToJumpTable = absTableEntry - (instrPtr + instr->size);

//calls need to be rewritten as relative jumps to the abs table

//but we want to preserve the length of the instruction, so pad with NOPs

uint8_t jmpBytes[2] = { 0xEB, distToJumpTable };

memset(instr->bytes, 0x90, instr->size);

memcpy(instr->bytes, jmpBytes, sizeof(jmpBytes));

}Jumps are more of a pain. There are a lot of different jump instructions that we might encounter, many of which are some flavor of a conditional jump. We can’t replace these instructions with a normal jmp because that could change the execution logic of our stolen bytes. Instead we need to rewrite the operands directly, so that these jumps will conditionally jump to the Absolute Instruction Table.

void RewriteJumpInstruction(cs_insn* instr, uint8_t* instrPtr, uint8_t* absTableEntry)

{

uint8_t distToJumpTable = absTableEntry - (instrPtr + instr->size);

//jmp instructions can have a 1 or 2 byte opcode, and need a 1-4 byte operand

//rewrite the operand for the jump to go to the jump table

uint8_t instrByteSize = instr->bytes[0] == 0x0F ? 2 : 1;

uint8_t operandSize = instr->size - instrByteSize;

switch (operandSize)

{

case 1: {instr->bytes[instrByteSize] = distToJumpTable; }break;

case 2: {uint16_t dist16 = distToJumpTable; memcpy(&instr->bytes[instrByteSize], &dist16, 2); } break;

case 4: {uint32_t dist32 = distToJumpTable; memcpy(&instr->bytes[instrByteSize], &dist32, 4); } break;

}

}The snippet below shows how these new functions should be added to BuildTrampoline(). Notice that we need to wait until after calling these new rewrite functions before we can increment the absTableMem pointer.

uint32_t BuildTrampoline(void* func2hook, void* dstMemForTrampoline)

{

X64Instructions stolenInstrs = StealBytes(func2hook);

uint8_t* stolenByteMem = (uint8_t*)dstMemForTrampoline;

uint8_t* jumpBackMem = stolenByteMem + stolenInstrs.numBytes;

uint8_t* absTableMem = jumpBackMem + 13; //13 is the size of a 64 bit mov/jmp instruction pair

for (int i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i) {

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

if (inst.id >= X86_INS_LOOP && inst.id <= X86_INS_LOOPNE){

return 0; //bail out on loop instructions, I don't have a good way of handling them

}

if (IsRelativeJump(inst)){

uint32_t aitSize = AddJmpToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem);

RewriteJumpInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem, absTableMem);

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

else if (inst.id == X86_INS_CALL){

uint32_t aitSize = AddCallToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem, jumpBackMem);

RewriteCallInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem, absTableMem);

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

//write stolen instruction (rewritten or otherwise) to trmapoline mem

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}

//write jump back to hooked func

free(stolenInstrs.instructions);

return uint32_t( (uint8_t*)absTableMem - dstMemForTrampoline);

}Step 5: Write the Jump Back to the Hooked Function’s Body

This has been a long process, but we’re almost there. Now we need to fill in the middle of the jump sandwich, and return our trampoline’s size. After all the work we’ve done so far, this last step doesn’t need much explanation. All we need to do is replace the comment in the snippet above with the following:

WriteAbsoluteJump64(jumpBackMem, (uint8_t*)func2hook + 5);When we stole the bytes from func2hook, we also replaced them with NOP instructions. This makes our life easier here, since the jump back to our hooked function doesn’t have to care about the number of bytes we stole. Jumping to the byte immediately after the hook’s jump is guaranteed to be safe.

Finally we return the byte count of our trampoline, so that InstallHook() can write the relay function into memory right after our trampoline bytes.

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunc, void** trampolinePtr)

{

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

void* hookMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

uint32_t trampolineSize = BuildTrampoline(func2hook, hookMemory);

*trampolinePtr = hookMemory;

//create the relay function

void* relayFuncMemory = (char*)hookMemory + trampolineSize;

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, payloadFunc); //write relay func instructions

//install the hook

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

const int32_t relAddr = (int32_t)relayFuncMemory - ((int32_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}aaaaand we’re done! The collapsebox below shows the full source for a program that uses this trampoline to hook a function. We’ve already talked about all the fun parts, so I’m going to leave it here without comment and move on to the grand finale.

Full Example of Trampoline Hooking a Function In The Same Process As The Hook Code

#include <stdio.h>

#include <cstdlib>

#include "capstone/x86.h"

#include "capstone/capstone.h"

#include <vector>

#include <Windows.h>

__declspec(noinline) void TargetFunc(int x, float y)

{

if (x > 0) printf("Target Func: x > 0\n");

}

void(*TargetFuncTrampoline)(int, float) = nullptr;

void HookPayload(int x, float y)

{

printf("Hook executed\n");

TargetFuncTrampoline(x + 1, y);

}

void* AllocatePageNearAddress(void* targetAddr)

{

SYSTEM_INFO sysInfo;

GetSystemInfo(&sysInfo);

const uint64_t PAGE_SIZE = sysInfo.dwPageSize;

uint64_t startAddr = (uint64_t(targetAddr) & ~(PAGE_SIZE - 1)); //round down to nearest page boundary

uint64_t minAddr = min(startAddr - 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMinimumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t maxAddr = max(startAddr + 0x7FFFFF00, (uint64_t)sysInfo.lpMaximumApplicationAddress);

uint64_t startPage = (startAddr - (startAddr % PAGE_SIZE));

uint64_t pageOffset = 1;

while (1)

{

uint64_t byteOffset = pageOffset * PAGE_SIZE;

uint64_t highAddr = startPage + byteOffset;

uint64_t lowAddr = (startPage > byteOffset) ? startPage - byteOffset : 0;

bool needsExit = highAddr > maxAddr && lowAddr < minAddr;

if (highAddr < maxAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)highAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr)

return outAddr;

}

if (lowAddr > minAddr)

{

void* outAddr = VirtualAlloc((void*)lowAddr, PAGE_SIZE, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (outAddr != nullptr)

return outAddr;

}

pageOffset++;

if (needsExit)

{

break;

}

}

return nullptr;

}

void WriteAbsoluteJump64(void* absJumpMemory, void* addrToJumpTo)

{

uint8_t absJumpInstructions[] = { 0x49, 0xBA, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x41, 0xFF, 0xE2 };

uint64_t addrToJumpTo64 = (uint64_t)addrToJumpTo;

memcpy(&absJumpInstructions[2], &addrToJumpTo64, sizeof(addrToJumpTo64));

memcpy(absJumpMemory, absJumpInstructions, sizeof(absJumpInstructions));

}

struct X64Instructions

{

cs_insn* instructions;

uint32_t numInstructions;

uint32_t numBytes;

};

X64Instructions StealBytes(void* function)

{

// Disassemble stolen bytes

csh handle;

cs_open(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64, &handle);

cs_option(handle, CS_OPT_DETAIL, CS_OPT_ON); // we need details enabled for relocating RIP relative instrs

size_t count;

cs_insn* disassembledInstructions; //allocated by cs_disasm, needs to be manually freed later

count = cs_disasm(handle, (uint8_t*)function, 20, (uint64_t)function, 20, &disassembledInstructions);

//get the instructions covered by the first 5 bytes of the original function

uint32_t byteCount = 0;

uint32_t stolenInstrCount = 0;

for (int32_t i = 0; i < count; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = disassembledInstructions[i];

byteCount += inst.size;

stolenInstrCount++;

if (byteCount >= 5) break;

}

//replace instructions in target func wtih NOPs

memset(function, 0x90, byteCount);

cs_close(&handle);

return { disassembledInstructions, stolenInstrCount, byteCount };

}

bool IsRelativeJump(cs_insn& inst)

{

bool isAnyJumpInstruction = inst.id >= X86_INS_JAE && inst.id <= X86_INS_JS;

bool isJmp = inst.id == X86_INS_JMP;

bool startsWithEBorE9 = inst.bytes[0] == 0xEB || inst.bytes[0] == 0xE9;

return isJmp ? startsWithEBorE9 : isAnyJumpInstruction;

}

bool IsRelativeCall(cs_insn& inst)

{

bool isCall = inst.id == X86_INS_CALL;

bool startsWithE8 = inst.bytes[0] == 0xE8;

return isCall && startsWithE8;

}

void RewriteJumpInstruction(cs_insn* instr, uint8_t* instrPtr, uint8_t* absTableEntry)

{

uint8_t distToJumpTable = uint8_t(absTableEntry - (instrPtr + instr->size));

//jmp instructions can have a 1 or 2 byte opcode, and need a 1-4 byte operand

//rewrite the operand for the jump to go to the jump table

uint8_t instrByteSize = instr->bytes[0] == 0x0F ? 2 : 1;

uint8_t operandSize = instr->size - instrByteSize;

switch (operandSize)

{

case 1: instr->bytes[instrByteSize] = distToJumpTable; break;

case 2: {uint16_t dist16 = distToJumpTable; memcpy(&instr->bytes[instrByteSize], &dist16, 2); } break;

case 4: {uint32_t dist32 = distToJumpTable; memcpy(&instr->bytes[instrByteSize], &dist32, 4); } break;

}

}

void RewriteCallInstruction(cs_insn* instr, uint8_t* instrPtr, uint8_t* absTableEntry)

{

uint8_t distToJumpTable = uint8_t(absTableEntry - (instrPtr + instr->size));

//calls need to be rewritten as relative jumps to the abs table

//but we want to preserve the length of the instruction, so pad with NOPs

uint8_t jmpBytes[2] = { 0xEB, distToJumpTable };

memset(instr->bytes, 0x90, instr->size);

memcpy(instr->bytes, jmpBytes, sizeof(jmpBytes));

}

uint32_t AddJmpToAbsTable(cs_insn& jmp, uint8_t* absTableMem)

{

char* targetAddrStr = jmp.op_str; //where the instruction intended to go

uint64_t targetAddr = _strtoui64(targetAddrStr, NULL, 0);

WriteAbsoluteJump64(absTableMem, (void*)targetAddr);

return 13; //size of mov/jmp instrs for absolute jump

}

uint32_t AddCallToAbsTable(cs_insn& call, uint8_t* absTableMem, uint8_t* jumpBackToHookedFunc)

{

char* targetAddrStr = call.op_str; //where the instruction intended to go

uint64_t targetAddr = _strtoui64(targetAddrStr, NULL, 0);

uint8_t* dstMem = absTableMem;

uint8_t callAsmBytes[] =

{

0x49, 0xBA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, 0xAA, //movabs 64 bit value into r10

0x41, 0xFF, 0xD2, //call r10

};

memcpy(&callAsmBytes[2], &targetAddr, sizeof(void*));

memcpy(dstMem, &callAsmBytes, sizeof(callAsmBytes));

dstMem += sizeof(callAsmBytes);

//after the call, we need to add a second 2 byte jump, which will jump back to the

//final jump of the stolen bytes

uint8_t jmpBytes[2] = { 0xEB, uint8_t(jumpBackToHookedFunc - (absTableMem + sizeof(jmpBytes))) };

memcpy(dstMem, jmpBytes, sizeof(jmpBytes));

return sizeof(callAsmBytes) + sizeof(jmpBytes); //15

}

bool IsRIPRelativeInstr(cs_insn& inst)

{

cs_x86* x86 = &(inst.detail->x86);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < inst.detail->x86.op_count; i++)

{

cs_x86_op* op = &(x86->operands[i]);

//mem type is rip relative, like lea rcx,[rip+0xbeef]

if (op->type == X86_OP_MEM)

{

//if we're relative to rip

return op->mem.base == X86_REG_RIP;

}

}

return false;

}

template<class T>

T GetDisplacement(cs_insn* inst, uint8_t offset)

{

T disp;

memcpy(&disp, &inst->bytes[offset], sizeof(T));

return disp;

}

//rewrite instruction bytes so that any RIP-relative displacement operands

//make sense with wherever we're relocating to

void RelocateInstruction(cs_insn* inst, void* dstLocation)

{

cs_x86* x86 = &(inst->detail->x86);

uint8_t offset = x86->encoding.disp_offset;

uint64_t displacement = inst->bytes[x86->encoding.disp_offset];

switch (x86->encoding.disp_size)

{

case 1:

{

int8_t disp = GetDisplacement<uint8_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= int8_t(uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address);

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 1);

}break;

case 2:

{

int16_t disp = GetDisplacement<uint16_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= int16_t(uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address);

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 2);

}break;

case 4:

{

int32_t disp = GetDisplacement<int32_t>(inst, offset);

disp -= int32_t(uint64_t(dstLocation) - inst->address);

memcpy(&inst->bytes[offset], &disp, 4);

}break;

}

}

uint32_t BuildTrampoline(void* func2hook, void* dstMemForTrampoline)

{

X64Instructions stolenInstrs = StealBytes(func2hook);

uint8_t* stolenByteMem = (uint8_t*)dstMemForTrampoline;

uint8_t* jumpBackMem = stolenByteMem + stolenInstrs.numBytes;

uint8_t* absTableMem = jumpBackMem + 13; //13 is the size of a 64 bit mov/jmp instruction pair

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < stolenInstrs.numInstructions; ++i)

{

cs_insn& inst = stolenInstrs.instructions[i];

if (inst.id >= X86_INS_LOOP && inst.id <= X86_INS_LOOPNE)

{

return 0; //bail out on loop instructions, I don't have a good way of handling them

}

if (IsRIPRelativeInstr(inst))

{

RelocateInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem);

}

else if (IsRelativeJump(inst))

{

uint32_t aitSize = AddJmpToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem);

RewriteJumpInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem, absTableMem);

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

else if (inst.id == X86_INS_CALL)

{

uint32_t aitSize = AddCallToAbsTable(inst, absTableMem, jumpBackMem);

RewriteCallInstruction(&inst, stolenByteMem, absTableMem);

absTableMem += aitSize;

}

memcpy(stolenByteMem, inst.bytes, inst.size);

stolenByteMem += inst.size;

}

WriteAbsoluteJump64(jumpBackMem, (uint8_t*)func2hook + 5);

free(stolenInstrs.instructions);

return uint32_t(absTableMem - (uint8_t*)dstMemForTrampoline);

}

void InstallHook(void* func2hook, void* payloadFunc, void** trampolinePtr)

{

DWORD oldProtect;

VirtualProtect(func2hook, 1024, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

void* hookMemory = AllocatePageNearAddress(func2hook);

uint32_t trampolineSize = BuildTrampoline(func2hook, hookMemory);

*trampolinePtr = hookMemory;

//create the relay function

void* relayFuncMemory = (char*)hookMemory + trampolineSize;

WriteAbsoluteJump64(relayFuncMemory, payloadFunc); //write relay func instructions

//install the hook

uint8_t jmpInstruction[5] = { 0xE9, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0, 0x0 };

const int32_t relAddr = (int32_t)relayFuncMemory - ((int32_t)func2hook + sizeof(jmpInstruction));

memcpy(jmpInstruction + 1, &relAddr, 4);

memcpy(func2hook, jmpInstruction, sizeof(jmpInstruction));

}

int main(int argc, const char** argv)

{

TargetFunc(argc, 0);

InstallHook(TargetFunc, HookPayload, (void**)&TargetFuncTrampoline);

TargetFunc(0, 0);

}Example 4: Using a Trampoline to Hook a Running Program

Like Po at the end of Kung Fu Panda, it’s time to put all our newfound skills to use and fulfill our destiny of becoming the dragon warrior.

The last example is going to use a trampoline to force mspaint to always use the color orange, no matter what color the user tries to select. This was shown in the gif at the start of article, but it’s been a long time since then, so here that gif is again:

Mercifully for us, we don’t need to go on an RVA fishing trip this time, because the function we want to hook is exported from a DLL. We’re going to install a hook into gdiplus.dll’s GdipSetSolidFillColor() function. Finding out that this was the right function to hook was pretty much the same process as the last mspaint example: lots of trial and error with breakpoints in x64dbg. A reverse engineer I am not.

So, here’s the plan:

- Write a hook payload function that intercepts calls to GdipSetSolidFillColor and replaces the incoming function arguments with the color orange.

- Put that payload in a DLL, along with all the hooking logic required to make it happen

- Inject that DLL into a running instance of mspaint

- Make beautiful artwork with the best color ever.

We’ve already exhaustively walked through a code example that used the same hooking logic that we need to use here. Rather than do that again, let’s focus on what’s different this time. Looking up GdipSetSolidFillColor() gives us this function signature:

GpStatus WINGDIPAPI GdipSetSolidFillColor(Gdiplus::GpSolidFill *brush, Gdiplus::ARGB color)Recall that the ARGB type is a uint32 with each byte representing a color channel. This means that all our payload need to do to make things orange is set some bits and pass the new ARGB value to the trampoline:

Gdiplus::GpStatus(*GdipSetSolidFillColorTrampoline)(Gdiplus::GpSolidFill* brush, Gdiplus::ARGB color);

Gdiplus::GpStatus GdipSetSolidFillColorPayload(Gdiplus::GpSolidFill* brush, Gdiplus::ARGB color)

{

Gdiplus::ARGB orange = 0xffff7700;

return GdipSetSolidFillColorTrampoline(brush, orange);

}This isn’t going to be enough to make ALL the possible painting tools spit out orange all the time. The paint can tool, spray paint brushes, etc will still use the colors selected. Our dll will just make most brushes always paint orange, which is good enough for me. It’ll also totally mess with the output of some brushes and make them operate weirdly too, which is fun in its own way.

Here’s a gif demonstrating some of the tools not painting orange, despite our dll being injected into paint:

The hooking logic that we include in the DLL is going to similar to the trampoline code we wrote for Example 3. The main difference is how we get a pointer to the function we want to hook.

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD ul_reason_for_call, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

if (ul_reason_for_call == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

HMODULE gdiPlusModule = FindModuleInProcess(GetCurrentProcess(), ("gdiplus.dll"));

void* localHookFunc4 = GetProcAddress(gdiPlusModule, ("GdipSetSolidFillColor"));

InstallHook(localHookFunc4, GdipSetSolidFillColorPayload);

}

return true;

}The FindModuleInProcess() function called above is similar to the GetBaseModuleForProcess() function that we used in a previous example, except that it can look for any loaded module by string name. The function is a bit long, so rather than paste it here, I’ve included it in the complete source for this example. The program used to inject this dll into paint is the same as the one we used before, but it’s also included below.

It took a while to get here, but we’re finally done Example 4! Go celebrate by making beautiful orange artwork!

Full Source For DLL Injector Program (click to expand)

//Injector_LoadLibrary is a dll injector that uses LoadLibraryA to inject a dll into a running process

// usage: Injector_LoadLibrary <process name> <path to dll>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <Windows.h>

#include <TlHelp32.h> //for PROCESSENTRY32, needs to be included after windows.h

void printHelp()

{

printf("Injector_LoadLibrary\nUsage: Injector_LoadLibrary <process name> <path to dll>\n");

}

void createRemoteThread(DWORD processID, const char* dllPath)

{

HANDLE handle = OpenProcess(

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATION | //Needed to get a process' token

PROCESS_CREATE_THREAD | //for obvious reasons

PROCESS_VM_OPERATION | //required to perform operations on address space of process (like WriteProcessMemory)

PROCESS_VM_WRITE, //required for WriteProcessMemory

FALSE, //don't inherit handle

processID);

if (handle == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not open process with pid: %lu\n", processID);

return;

}

//once the process is open, we need to write the name of our dll to that process' memory

size_t dllPathLen = strlen(dllPath);

void* dllPathRemote = VirtualAllocEx(

handle,

NULL, //let the system decide where to allocate the memory

dllPathLen,

MEM_COMMIT, //actually commit the virtual memory

PAGE_READWRITE); //mem access for committed page

if (!dllPathRemote)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not allocate %zd bytes in process with pid: %lu\n", dllPathLen, processID);

return;

}

BOOL writeSucceeded = WriteProcessMemory(

handle,

dllPathRemote,

dllPath,

dllPathLen,

NULL);

if (!writeSucceeded)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not write %zd bytes to process with pid %lu\n", dllPathLen, processID);

return;

}

//now get address of LoadLibraryW function inside Kernel32.dll

//TEXT macro "Identifies a string as Unicode when UNICODE is defined by a preprocessor directive during compilation. Otherwise, ANSI string"

PTHREAD_START_ROUTINE loadLibraryFunc = (PTHREAD_START_ROUTINE)GetProcAddress(GetModuleHandle(TEXT("Kernel32.dll")), "LoadLibraryA");

if (loadLibraryFunc == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not find LoadLibraryA function inside kernel32.dll\n");

return;

}

//now create a thread in remote process that loads our target dll using LoadLibraryA

HANDLE remoteThread = CreateRemoteThread(

handle,

NULL, //default thread security

0, //stack size for thread

loadLibraryFunc, //pointer to start of thread function (for us, LoadLibraryA)

dllPathRemote, //pointer to variable being passed to thread function

0, //0 means the thread runs immediately after creation

NULL); //we don't care about getting back the thread identifier

if (remoteThread == NULL)

{

fprintf(stderr, "Could not create remote thread.\n");

return;

}

else

{