Comparing Uniform Data Transfer Methods in Vulkan

Lately I’ve been trying to wrap my head around Vulkan. As part of that, I’ve been building a small Breakout clone (github) as a way to see how the pieces of the API fit together in a “real” application.

When I’m starting to learn a new graphics API, the thing that I try to focus on is getting used to all the different ways to send data from the CPU to the GPU. Since my Breakout clone didn’t have textures, or meshes (really) to speak of, that left the per frame uniform data for each object on screen.

The "Playable" version of the Breakout Clone

The "Playable" version of the Breakout Clone

Looking at a few vulkan examples I could find, and taking a quick glance through the API, I settled on 5 different options for getting my uniform data sent to the card:

- Using push-constants

- Using 1 VkBuffer and keeping it mapped all the time

- Using 1 VkBuffer and mapping/unmapping per frame

- Using multiple VkBuffers, and keeping them all mapped

- Using multiple VkBuffers, and mapping/unmapping every frame

All the guidelines out there are pretty clear when they say to use push-constants for data that has to change on a per-object basis every frame, but given that push constants have a size limit, it made sense to give each of the above approaches a whirl, since they conceivably all will have their place in a large application.

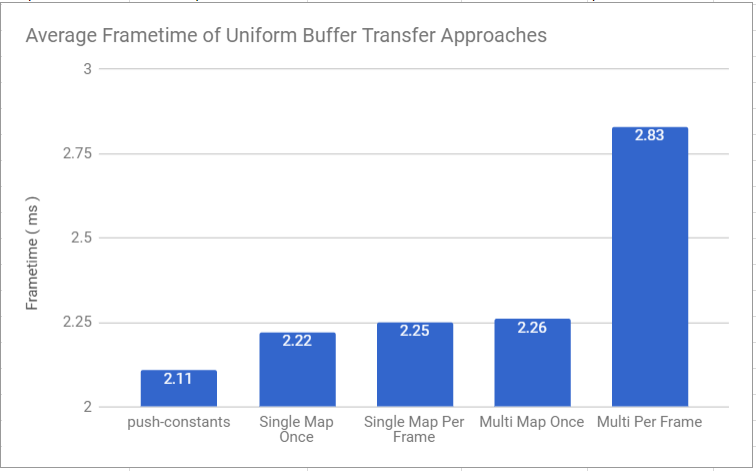

So, in the interest of whirling, I put a branch in my repo for each, and then tracked the average frame-time of each to see how much faster or slower each approach was.

However, Breakout is really not a good test for a GTX 1060, and with 500 blocks on screen, I was running every test at < 1 ms per frame. The times were so small, that even between runs of the exact same version of the program, the results were too varied to be much use (since even a change in measured time of 1/100th of an ms became significant). To make things a bit easier to work with, I added a mode to the game which rendered 5000 blocks at a time.

which admittedly looked sorta ridiculous

which admittedly looked sorta ridiculous

This produced much more stable results (ie/ could be reproduced in multiple runs), which I want to provide here to give context to the rest of this blog post.

The big takeaway here is that mapping memory is a really slow process, so if you need something mapped, keep it that way for as long as you can. This is likely not news to anyone except me, since I’ve been living in mobile engine land for my whole career and really haven’t had to worry about that. Oh, and the guides were right, you should totally use push constants when you can. If you can’t use them, there’s a slight advantage to packing multiple objects worth of data into a single buffer, vs giving every object it’s own.

With that in mind, I want to walk through the implementation details of each approach, because I wish something like that had existed before I started down this rabbit hole. If you were only interested in the performance results, you can stop reading and go about your life :) If you’re scratching your head as to how to do one or more of these things, join me below!

Preliminary info

In order to make much sense of the code I’m going to share, it will be helpful to understand that my code stores uniform data that will be sent to the GPU in a struct called PrimitiveUniformObject, which directly maps to the layout of the uniform data in the shader:

//CPU

struct PrimitiveUniformObject

{

glm::mat4 model;

glm::vec4 color;

};

//glsl

layout(set = 0, binding = 0) uniform PER_OBJECT

{

mat4 mvp;

vec4 col;

} obj;Hopefully that makes sense! I’m going to try to keep all the snippets I share abbreviated enough that you otherwise don’t need to care about how I structured things, but I couldn’t get around telling you about this tiny bit.

I’m also going to assume that you’re at least at the level I was when I started this project, that is, you’ve gone through vulkan-tutorial.com, and therefore understand how to allocate a VkBuffer. If you aren’t there yet, click the link to the tutorial and come back in a few hours. Things will make much more sense.

Multiple, Unmapped Buffers

Let’s start by talking about the approaches that felt most intuitive for me right off the bat, giving each drawable entity (which my code calls a Primitive) it’s own VkBuffer to store it’s own uniform data, and a VkDescriptorSet to know about that buffer:

struct PrimitiveInstance

{

vec3 pos;

vec3 scale;

vec4 col;

VkBuffer uniformBuffer;

VkDescriptorSet descSet;

VkDeviceMemory bufferMem;

int meshID;

};My project was simple enough (and my gpu forgiving enough) that I could get away with doing a VkDeviceMemory allocation for every primitive. On a larger project you’d have to do something smarter than that.

Since the entirety of the data stored in the VkBuffer is going to get updated every frame, and we’re going to update the data with a single write to the buffer data, I allocated the VkBuffers with host coherent memory, which makes things nice and easy when it’s time to update the data:

//abbreviated code:

PrimitiveUniformObject puo;

puo.model = VIEW_PROJECTION * (glm::translate(pos) * glm::scale(scale));

puo.color = col;

void* udata = nullptr;

vkMapMemory(device, bufferMem, 0, sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject), 0, &udata);

memcpy(udata, &puo, sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject));

vkUnmapMemory(device, bufferMem);Since we’ve already taken a look at the performance graph, we know that mapping/unmapping the buffer for each Primitive, every frame, is a performance killer. We can work around that with the next approach and get much better results.

Multiple, Always Mapped Buffers

To make the multiple buffer approach faster, all we need to do is to add one more variable to the PrimitiveInstance struct:

struct PrimitiveInstance

{

vec3 pos;

vec3 scale;

vec4 col;

VkBuffer uniformBuffer;

VkDescriptorSet descSet;

void* mapped;

int meshID;

};In this approach, when a primitive was created, the data for their buffer was immediately mapped, and the address stored in the mapped pointer above. Note that the PrimitiveInstance struct doesn’t contain a PrimitiveUniformObject, those get created per frame by combining the easier to work with variables we have here.

//abbreviated code:

PrimitiveUniformObject puo;

puo.model = VIEW_PROJECTION * (glm::translate(pos) * glm::scale(scale));

puo.color = col;

memcpy(mapped, &puo, sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject));Then, all that’s needed is to submit each object’s descriptorSet to the rendering function, and pass the right one to vkCmdBindDescriptorSets at the right time. As you saw in the graph earlier, this approach was the slowest of the three approaches that didn’t involve mapping/unmapping data every frame.

In the above code, I don’t need to call vkflushmappedmemoryranges or similar because the buffer memory was allocated with the VK_MEMORY_PROPERTY_HOST_COHERENT_BIT flag set. Without that, you’d have to manually tell vulkan when you changed the data at that pointer. Host coherent memory is very likely slower than not the alternative, but for buffers which are completely changed every frame, I’m not sure there’s much of a difference.

I haven’t tested out anything using non-host coherent memory though, so I reserve the right to be totally wrong about that.

Single Dynamic Uniform Buffer

The second approach I tried was to allocate a single VkBuffer which was large enough to store the uniform data for every object inside it, treating the buffer’s contents as an array of uniform data. Since in my case, I was submitting an array of mesh ids alongside the uniform data, this meant that I didn’t need to store any extra info in the primitive instance struct. As long as both arrays were in the same order, the right mesh would get drawn with the right uniform data.

struct PrimitiveInstance

{

vec3 pos;

vec3 scale;

vec4 col;

int meshID;

};One caveat to this approach is that the data stored in the VkBuffer has to be memory aligned to your GPU. In my case, I was already getting my VkPhysicalDeviceProperties when I initialized everything, so that data was easily accessible. With that alignment data, you can then figure out exactly how big your VkBuffer has to be:

size_t deviceAlignment = deviceProps.limits.minUniformBufferOffsetAlignment;

size_t uniformBufferSize = sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject);

size_t dynamicAlignment = (uniformBufferSize / deviceAlignment) * deviceAlignment + ((uniformBufferSize % deviceAlignment) > 0 ? deviceAlignment : 0);

size_t bufferSize = uniformBufferSize * primitiveCount * dynamicAlignment;Once you know the alignment you need, you can use Windows’ aligned_malloc function to actually get an aligned block of memory, which you can then memcpy into the vkbuffer’s mapped pointer.

uniformData = (PrimitiveUniformObject*)_aligned_malloc(bufferSize, dynamicAlignment);Since the PrimitiveUniformObject struct itself has no notion of alignment, you have to space your writes into buffer memory accordingly:

//abbreviated code

int idx = 0;

char* uniformChar = (char*)uniformData;

for (const auto& prim : primitives)

{

PrimitiveUniformObject puo;

puo.model = VIEW_PROJECTION * (glm::translate(prim.pos) * glm::scale(prim.scale));

puo.color = prim.col;

memcpy(&uniformChar[idx * dynamicAlignment], &puo, sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject));

idx++;

}Likewise, when you allocate your VkBuffer, you’re going to want to request a buffer of size dynamicAlignment * number of primitives, and you’ll want to make sure you get memory that comes from a descriptorPool of type VK_DESCRIPTOR_TYPE_UNIFORM_BUFFER_DYNAMIC.

With all of that set up, you can then copy your frame data to the uniform buffer like so:

void* udata = nullptr;

vkMapMemory(device, buffer.deviceMemory, 0, dynamicAlignment * PRIM_COUNT, 0, &udata);

memcpy(udata, uniformData, dynamicAlignment * PRIM_COUNT);

vkUnmapMemory(device, buffer.deviceMemory);And finally, you need to pass an offset in your calls to vkCmdBindDescriptorSets. This offset tells vulkan where in the single buffer’s data to grab each object’s individual uniform data. Since it’s a byte offset, you’ll need to have the dynamicAlignment value we calculated earlier handy:

for (int i = 0; i < PRIM_COUNT; ++i)

{

uint32_t dynamicOffset = i * static_cast<uint32_t>(dynamicAlignment);

vkCmdBindDescriptorSets(commandBuffer,

VK_PIPELINE_BIND_POINT_GRAPHICS,

pipelineLayout,

0,

1,

&descriptorSet,

1,

&dynamicOffset);

// rest of per object draw code goes here

}That should be enough to get you going, but we can make this faster too.

Always Mapped Single Buffer

Just like the multi-buffer approach, we can speed up the single buffer solution by keeping that buffer always mapped. Since we only have one buffer, this is a trivial change to the code. If you wanted, you could even just do it inside your update function like this:

static void* udata = nullptr;

if (!udata)

{

vkMapMemory(device, buffer.deviceMemory, 0, dynamicAlignment * PRIM_COUNT, 0, &udata);

}

memcpy(udata, uniformData, dynamicAlignment * PRIM_COUNT);Of course, you probably shouldn’t do it like this, but there’s no performance reason not to, so I’m going to back away slowly from discussing code quality issues now.

Push Constants

To finish things off, let’s take a look at our big winner from the performance tests. Push constants are great for data that updates this frequently because you don’t actually need to allocate any buffers for it. This also means that we need to do a few things differently from the previous 4 approaches we’ve looked at, like changing how we declare our uniform data struct in glsl:

layout(push_constant) uniform PER_OBJECT

{

mat4 mvp;

vec4 col;

} obj;Next, instead of creating any VkBuffers, when we create our pipeline layout, we need to specify a push constant range:

VkPushConstantRange pushConstantRange = {};

pushConstantRange.offset = 0;

pushConstantRange.size = sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject);

pushConstantRange.stageFlags = VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT;

VkPipelineLayoutCreateInfo pipelineLayoutInfo = {};

//..other init code here

pipelineLayoutInfo.pSetLayouts = &descriptorSetLayout; // still need this

pipelineLayoutInfo.pushConstantRangeCount = 1;

pipelineLayoutInfo.pPushConstantRanges = &pushConstantRange;Like the comment above says, even when using push constants, you still need to provide a descriptorSetLayout to specify how the uniform data is going to be laid out in memory. You just don’t actually need to make any descriptorSets to actually pass that data to the shader.

Instead, where you might otherwise call vkCmdBindDescriptorSets, you do the following:

for (int i = 0; i < PRIM_COUNT); ++i)

{

vkCmdPushConstants(

commandBuffer,

pipelineLayout,

VK_SHADER_STAGE_VERTEX_BIT,

0,

sizeof(PrimitiveUniformObject),

&uniformData[i]);

// rest of per object draw code goes here

}That should cover it (assuming I haven’t missed a step). Given the option, push constants feel a lot cleaner for passing small bits of data to shaders, which makes sense given that they’re tailor made for that purpose. It is nice to have the most performant option we have, also be the easiest to work with.

Conclusion

That wraps up the implementation details for everything. To get a sense of when to use each approach, I recommend you check out NVidia’s Vulkan Shader Resource Binding page.

I’m a complete beginner with Vulkan, so if you see anything weird or just plain wrong in this post, please send me a message on Twitter, I would love to hear from you! Likewise, if there’s a resource out there that’s helped you get a handle on Vulkan, please pass it along.

Until next time!

In case reviewing testing methods is your thing, here's how I got the numbers in all the graphs in this post: